- Home

- Seery, Daniel;

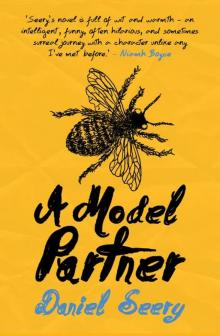

A Model Partner

A Model Partner Read online

A Model Partner

Daniel Seery

For Sonia

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter 1

It was March when Tom Stacey met the woman from Donaghmede who couldn’t stop crying. The date had been set up by an agency, Happy Couples, a business owned by two middle-aged women, both silver-haired, both wearers of glasses, Anna slightly more dumpy than Martha but without the facial hair which Martha tries to hide under sludgy-looking foundation. Their office, a single room above a dental surgery near the Artane Roundabout, is the cramped type, yellowed blinds on the window, desks side by side, two sturdy grey filing cabinets and a wooden unit where thin documents slouch and bend on each shelf.

They are believers in love, Martha and Anna, devout followers. And a couple of years ago Tom would have never set foot in a place like this but in some ways Tom is a believer himself, a believer in last chances. He would never admit this to himself, never clasp his hands together and rock back and forth urging himself on with a mantra.

Last shot Tommy boy, last one in the bag.

But there’s only so long that emptiness can stay unfilled and at the time he joined the agency Tom was starting to worry about what was going to fill his emptiness.

So he walked in off the street and he took the single chair that was neither in front of Martha’s desk nor in front of Anna’s but somewhere in between and which made Tom feel exposed and a little unsure of where to look. He rested his hands on his lap and waited for their guidance.

They sat with identical straight-backed poses, heads angled to the right and that little half-smile that comes on people when they are dealing with those who they pity.

‘We know what it’s like,’ Martha said.

‘We’ve been there before,’ Anna added in an identical tone.

‘It can be difficult to meet new people.’

Martha offered an exaggerated slump of the shoulders and a put-on sad face or what Anna would later refer to as a ‘frownie face’.

They settled on the woman from Donaghmede. The crier. It was to be his first date with the agency and the ladies congratulated each other on the find and then congratulated Tom on what was to be his perfect match. Tom was shown her picture. She was pretty in a stylised, conventional way, her hair layered in varying shades of brown, her eyebrows the barest of lines, large blue eyes and thin face. Two weeks later, in real-life physical form she would resemble this photograph only slightly and Tom would think of those travel guides that are on a special stand in his local library, the ones where all the photographs have been taken on a bright sunny day, and he would think how different a place can look with an overcast sky in the middle of winter.

He met her in a pub on Capel Street, a place with large arch windows and a recently constructed dining area. Cutlery rested on white paper napkins and the menus were laminated and sandwiched between glass salt shakers and grubby bottles of tomato ketchup. He arrived first and requested the table nearest the door, moving his chair so that when he sat down he was directly facing the exit. She arrived ten minutes late. She shed her first tears after the starter and by the time the main course landed on the table she could hardly speak. She would inhale rapidly a number of times at the start of each sentence and make a stammering noise at the back of her throat, in some ways like a Cortina his grandfather once owned, a car which would choke over and over on cold mornings before the engine would eventually catch and grumble to life.

She said she was a primary school teacher and that she was depressed, going as far as to call herself a ‘puddle’.

‘I’m a puddle,’ she blubbered. ‘Nobody wants to be anywhere near a puddle.’

This would stay with Tom long after the date ended. A puddle. There is something deeply sad about puddles, he would think to himself.

‘Try not to worry about it,’ Tom had said. ‘Things will get better. They always get better.’

At one point he almost touched her hand. It looked so delicate and soft resting on the table. He reached across but lost his nerve at the last moment, instead jilting his hand to the right, sending the sauce bottle into a precarious wobble.

They didn’t agree to a second meet that evening but Tom did ask Martha a few weeks later how the woman was getting on. Martha gave a flight-attendant type smile and said that ‘Everyone is entitled to their privacy and if a particular client decides they do not want to see another particular client then it is best for all concerned to leave it in the past.’

Tom didn’t press any further.

His second date wasn’t as bad as the first but Tom laughed a little too loud at her jokes and asked her if she was okay too many times. As the night wore on she became standoffish and the noise of chewing became more audible and the clink of cutlery on plates all too uncomfortable in the silence. There have been plenty of dates since then, all as unsuccessful, and Tom is beginning to wonder if this dating agency is the best way to go.

‘Tom,’ Martha says when he enters the office. She folds her arms and sits forward. ‘How are you keeping?’

He notices the strain of her smile, the half-glance to her colleague. Anna stands and retrieves a file from the cabinet behind her while Tom takes a seat.

‘How did it go last night with …’ Anna rifles through the files for a couple of seconds, stops and scrolls her finger downward. ‘Ah, with Joyce. The lady from, um, Cabra Park.’

‘The Spark from the Park!’ Martha suddenly shouts and claps her hands together.

They both howl.

Tom waits for them to finish.

‘We didn’t really get on,’ he says and recalls the woman from the previous night, attractive, pallid skin and shoulder-length mousey hair that she had a habit of fidgeting with. The date was uneasy. She kept her head down for most of it, refusing to look him in the face, played with the food on her plate. It gave him plenty of time to notice the skinniness of her arms, the six tiny holes along the edge of her ear, relics of a more extreme lifestyle of piercings and God knows what else.

Tom tried his best to make the date a success. Twenty-one failed dates can do that; they can drive a person to make an effort. He talked about this and that, the food and service, the traffic in Dublin and the price of drink. This received little response so he talked about the book he was reading, a book about love and beauty that he had found in a second-hand bookshop. She didn’t seem interested in the changing nature of beauty, in the societal benefits that come with being beautiful or his claims that in the sixteenth century people believed that ugliness and deformity were signs of inherent evil.

‘Imagine that. Thinking that you are evil just because you have a mono-brow or something,’ he joked.

She didn’t laugh and she did

n’t even look up when he revealed that some people have a fear of ugliness.

‘Cacophobia,’ he said and nodded, waiting for a reaction. She continued to play with her food. ‘Where venustraphobia,’ he muttered, ‘is the fear of beautiful women. I’d imagine that’s much more common.’

As the evening wore on Tom couldn’t help but see fragility behind her quiet beauty. He didn’t ask her if she would like to go for a drink afterward and she walked off without offering him a kiss on the cheek. Her departure was so quiet that he wasn’t even sure she had said goodbye to him.

‘God, I thought you two would have made a nice match,’ Martha says.

‘Me too,’ Anna agrees. ‘But don’t worry. There are plenty more fish in the books.’ She flicks through her folder. ‘There are certain things that make two people incompatible. But all you need is to find the one person that is compatible. That’s the good thing Tom. You only need one woman and you only need to find her once.’

Tom has heard this before. She speaks and he drifts, becomes distracted by the disorganisation of the desks, the uneven nature of the furniture, a picture on the wall that is clearly askew. Not mildly askew. Completely askew.

Christ, they might as well have hung it upside down.

There is a stain on Anna’s sleeve, red, roughly the shape of Madagascar, an island which has been the focus of a series of documentaries he has enjoyed recently. He couldn’t say for sure but it is most probably tomato ketchup and it most probably smells of vinegar and it will probably stay on that sleeve even after the blouse has been washed. He follows the mark as she talks.

‘And I know that sometimes it’s hard to keep the head up. But just remember. It only has to work once,’ Anna makes notes on a page in the folder.

That smell, Tom thinks.

That stain.

The blob of sauce falling from the bottle.

The slurp as the air replaces the wet gloop.

Splat as it lands.

Splat as it drips.

Splat.

‘Splat.’

‘Sorry?’ Anna says.

‘Sorry?’ Tom wrinkles his brow.

‘Did you say something Tom?’ Anna asks without looking up.

‘No, I don’t think so.’

‘Could have sworn you said something,’ she turns a page over and writes some more notes.

Tom reddens, looks away from Anna.

‘You need to go out more,’ she says and looks up at Tom. ‘Have you been going out at all?’

‘It’s difficult to get the time,’ he eventually responds.

‘Well, let me just stop you there,’ Anna says. ‘If you don’t have time to go out now then how are you going to have time for a lady in your life?’

Tom understands that he would have a lot more time on his hands if he didn’t have to go out on dead-end dates.

‘You need to get out,’ Anna stresses her point by chopping the air with her hand. ‘It’s important that you build a good social life. Have you even been looking for opportunities to go out?’

‘Yeah, of course,’ Tom nods quickly. ‘There’s some work thing on soon. I suppose I could go to that.’

‘A work outing. Perfect.’ Anna makes a note of this in a space in the folder. ‘You have plenty going for you Tom. You’re independent and you have a job. You’re relatively handsome too. Just try not to worry so much about the little things.’

Tom arches an eyebrow.

‘You know,’ Anna says. ‘The little details.’

‘There have been some complaints,’ Martha says quickly, like it is something that she has been trying to hold in for quite a while. ‘From some of the women.’

Anna’s eyes widen.

‘Look, we realise that everyone is different,’ she says while throwing Martha a swift look.

Martha merely taps a page which she has removed from her own folder.

‘The furniture,’ Martha says.

‘People can become set in their ways,’ Anna tries to talk over her.

‘The cutlery,’ Martha continues. ‘The location of the table.’

‘It’s just that relationships are about give and take,’ Anna increases the volume.

‘Grammar,’ Martha says. ‘Doors. Hair.’

‘Sometimes you have to give a little,’ Anna says.

‘Hair?’ Tom turns to Martha. ‘I’ve never mentioned I had a problem with hair.’

Martha tips her glasses forward and reads from the page.

‘“He asked me how many times I washed my hair,”’ she says. ‘“He then informed me that when it comes to head lice, they don’t mind if your hair is clean or dirty.”’

‘You should be more careful about what you say,’ Anna clenches her hands together and bends toward him.

‘I was only saying that she had nice hair,’ Tom says.

‘Why didn’t you just say that? You have nice hair. That’s all you had to say,’ Anna says.

‘I did say that.’

‘“Girls are more likely to be infested by head lice than boys,”’ Martha reads. ‘“I’m not sure what he meant by this. I don’t have head lice.”’

‘Up to four times more likely,’ Tom says.

Martha shakes her head.

‘They need to have the same interests as me,’ Tom defends himself, pats his chest with an open hand as he speaks. ‘It’s not about head lice or cutlery. It’s about having the same interests as me.’

‘Sandra Lyons,’ Anna says, her finger scrolling down a page. ‘She’s forty-one. A little bit older than you but that shouldn’t matter. It says here that she likes reading.’

‘She likes reading what?’ Tom asks.

‘I’m guessing books,’ Martha says in a dour tone.

‘What type of books?’ Tom asks. ‘What type of authors? Jesus, sure she might only read the RTÉ bloody Guide.’

‘Tom. There’s no need for that language,’ Anna says. ‘And there’s nothing wrong with the RTÉ Guide,’ she mutters afterward.

‘I’m sorry. It’s just that,’ Tom shrugs and exhales. ‘I don’t know. You say not to worry about the little things but it’s all about the little things.’

Anna offers him a photograph.

Tom takes it, his mouth tightens and he shakes his head slightly.

‘It’s only a headshot.’

‘We’ve been over this,’ Martha says. ‘A headshot is enough.’

‘Besides,’ Anna says. ‘Body shape shouldn’t be that important.’

Tom bows his head and rubs his neck. He doesn’t mean body shape. He is thinking of a couple of his dates. They were nail-biters. The name itself brings up a horrible image of a woman nibbling away at her fingers, pieces of nails thrown outward. And the noise, the clickety-click as her head moves back and forth like the carriage on a typewriter. He shivered when he first caught sight of those kind of nails on a date, nibbled down so far it looked as if they were receding into the fingers. And then that’s all he could see for the whole date. This made him think that a headshot isn’t enough. There should be a shot of the nails, the toenails too and a shot of the ears, taken with a suitable flash just to be sure that they are good and clean.

‘Maybe the form needs more detail,’ Tom says. It is something that has been floating around his head for a time now but only really anchors when the words have left his mouth.

Needs more detail.

Of course.

The more detail, the less chance of error.

‘Subcategories or something,’ he thinks aloud. ‘Like imagine if they knew that I liked reading about history or if they realised that they watched the same documentaries as me, I don’t know, if they found the same things funny maybe I wouldn’t have to go on a million dates to find the right woman. If she knew what I wanted it would reduce the error factor.’

‘And if you knew,’ Martha says.

‘What?’

‘If you knew what you wanted that would help too.’

Tom shakes his head.

/>

‘What do you want Tom? You have to tell us. You come in here and you explain what went wrong with your dates and what you think is wrong with the service. You want everything and you want nothing at the same time. Well, I’m sorry Tom, we just can’t supply everything and nothing.’

‘I want to find someone,’ Tom says.

‘I know Tom, everybody who comes in here wants to find someone. But what someone do you want? Who is your ideal woman?’

Tom crosses his legs and looks upward, to the grille in the ceiling tiles. He tries to think of what he wants in his ideal woman but there is nothing there. All he sees is the dust which lines each section of the grille. And the third metal bar from the top. It is bent slightly and, in his mind, it has ruined the whole shape of the grille.

Chapter 2

Tom knew the chair was worth saving as soon as he saw it. He found it in a skip around the time he joined the agency, the base balanced on the rusted lip, fabric balding and torn, front legs hanging over the side like a mistreated animal trying to escape its confines. Despite its appearance and without even thoroughly inspecting it Tom had a feeling about that chair. It owned such clean, straight lines, was angled in all the right places, that Tom rescued it from the skip and brought it home.

Later that day, after close inspection, he would consider whether he had acquired some natural skill for measuring objects with the naked eye because the chair was indeed perfect for his bed-sit. And for a couple of weeks afterward, in the time that he spent mending it, the notion that he should hone and improve this natural measuring ability entered his head and he would debate whether he was destined for a career in this kind of area. He imagined himself on a television show, a glittering set and a shiny host.

‘Tom Stacey, everybody.’

He saw himself perched on a black leather armchair facing the audience, a number of objects separating them, lined in a row. Tom’s challenge was to guess the height and width.

‘The antique table Tom.’

‘Height 88 centimetres, width 105 centimetres.’

‘Pen.’

‘14 centimetres in length, 0.8 centimetres in diameter.’

A Model Partner

A Model Partner